Flag

of the United Suvadive Republic |

External

trade in the Maldives had largely passed through Malé,

with some exceptions. A few influential families in the Northern

Atolls and most merchants in the Southern Atolls of Addu and Huvadu

had, until relatively recently, by-passed Malé and traded

directly with ports in India, Ceylon and the East Indies.

Lack

of communication between Malé and the South, in particular,

had meant that the central authorites could do little to prevent

this. There was no effective means of taxing the trade that did

not pass through Malé. For a very long time the central

authorities were content with the status quo.

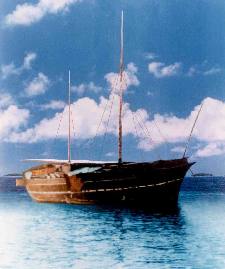

An

Addu trading vedi the Yaahumbaraas

sunk by the Imperial Japanese Navy

during World War II. The survivors

sustained much ordeal in Singapore |

The

affluence of the Addu and Huvadu merchants was always resented

by the mercantile classes in Malé.

World

War II presented the central authorities backed by Malé

merchants, their first opportunity to address this state of affairs.

By then, the Addu and Huvadu traders' main trading ports had long

been Colombo and Galle in Ceylon (Sri Lanka). Passport requirements

imposed by the Dutch who ruled Batavia (Indonesia) had long spelt

an end to the ancient Aceh trade. Wartime perils discouraged people

from venturing out to British Bengal.

With

the co-operation of the British authorities, Maldive diplomats

stationed in Colombo managed to monitor and control the movements

of the Southern merchants. For the first time in living memory,

in 1947, Maldivians travelling to Ceylon and other British possessions

in the region were required to carry passports and visas issued

in Malé. Both were issued by Maldive authorities. That

spelt an end to the direct external trade out of the South. The

central authorities had finally exerted control over the livelihoods

of the Southern merchants. This was bitterly resented in the South.

The

control over trade enhanced the opportunity to tighten other controls.

For long it had been rather difficult for the central authorities

to fully enforce the vaaru (poll tax) and the varuvaa

(land tax) on the South. The control over trade had made it easy

to enforce these taxes as well. This too led to resentment.

In

1944 British troops and support personnel were stationed in Gan

and Hithadoo in Addu Atoll. The local population were denied any

direct trade or bartering with the British, who included many

British Indians. Militia officers from Malé were stationed

in Addu to ensure that even the barter of single coconuts or limes

were transacted through the government.

The

disgusting behaviour of the two leading militiamen, Buchaa Hassan

Kaleyfan and Dada Kassim Kaleyfan infuriated the mild mannered

Addu aristocracy. The Addu aristocracy was descended from exiled

kings (see

Hithadhoo

Royal Connection)

and

the cream of the Maldive intelligentsia. A number of them had

served as chiefs justice in Malé over the centuries. In

the households of the royalty and the nobility in Malé,

the Addu aristocrats had always enjoyed a more privileged status

than the likes of Buchaa and Dada who were lower class officials.

The

arrest and physical assault on Ahmed Didi son of Elha Didi, a

member of one of the leading families in Hithadoo by Buchaa was

the final blow on the uneasy situation between the militia and

the locals.

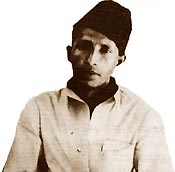

His

Excellency Abdullah Afeef Didi

President of the Republic, United

Suvadive Republic

|

A

mob rose up against Buchaa Hassan Kaleyfan who took refuge at

the British barracks. When the situation calmed down, the central

authorities rounded up alleged conspirators of the uprising. Buchaa

Hassan Kaleyfan's version of events prevailed at the investigations.

Among those convicted and sentenced to public flogging included

Abdulla Afeef Didi son of Ali Didi son of Elha Didi of Hithadoo.

Afeef Didi was a highly educated intellectual who spoke both English

and Arabic fluently. He was the translator to the British and

the most respected young individual in Addu at that time.

Public

flogging called burihan negun (literally, removing the

skin off the back) involved being simultaneously beaten by two

sets of cat-o-nine-tails until the victim was covered in blood,

then chilli paste rubbed into the wounds that covered most of

the area of the back between the shoulders down to the lower legs.

[Note: in

current Maldivian, buri may mean just the back, butt or

even anus. However, it may also mean the greater part of one's

behind. Burikarhi is the area betwen the shoulder and the

waist]

|

A

British Officer stationed in Gan in 1957 wrote to Majid

as follows:

"I

have the warmest memories and respect of the Addu people.

I admired the cheerfulness of the men, their prowess as

mariners and their acceptance of new ideas and probably

strange cultures. I recall the Elders, poised and sage;

the women beautifully clad and wearing gold embellishments,

and the eagerness of the children. I recall the immaculately-maintained

village streets, the incredible sunsets and the overall

beauty of the Maldives. Long may it be!"

The

officer prefers to remain anonymous

|

Wartime

British occupation of Addu ended in 1944. The escalation of the

Cold War saw the return of the British in 1957.

Mass

relocation of whole communities resulted from the evacuation of

Gan to build the British staging post.

The

wartime ban on direct trading between the British and the Addu

locals was re-imposed by the central authorities.

The

reluctance of the Maldive legislature to ratify the 100-year lease

of Gan and Maamendu in Hithadu infuriated the British authorities.

The civilian British contractor in Gan actively fostered the notion

of breaking away from central rule.

Under

the new accord with the central authorities, the British were

allowed to employ Addu people in their facilities. The income

from this and the luxury goods available to the workers together

with the encouragement from the civilian contractor persuaded

the locals to act.

Towards

the end of 1957, the mild-mannered Prime Minister Eggamugey Ibrahim

Faamuladeyri Kilegefan was forced to resign and the Sultan appointed

Velaanaagey Ibrahim Nasir (later Rannabandeyri Kilegefan) to that

position. Nasir was not conciliatory like his predecessor and

at the end of 1958, ordered the British to halt all construction

work in Addu. This was too much to bear for the civilian contractor.

Nasir

appointed Abdulla Afeef Didi as liaison officer between the British

and the locals.

In

October 1958, a Hithadoo mob threatened to attack govenment officials,

but was suppressed by British militay police.

On

New Year's Eve of 1959 the government announced a new tax on boats.

This sparked riots in Hithadoo which quickly spread. In the early

hours of 1959, government facilities were attacked and officials

forced to the security of British-controlled areas. Abdulla Afeef

Didi actually warned the leading officials of the impending disaster.

The

British did not do much to quell the unrest. A British soldier

actually pushed a box of matches towards a rioter encouraging

government facilities to be set ablaze.

On

3 January 1959, a delegation arrived in Gan and informed of the

declaration of independence to the British. Initially Abdulla

Afeef Didi took no part in this, but the British insisted on a

trustworthy leader being appointed before they would back the

rebellion.

Afeef

Didi was persuaded to take on this role when the British offered

him in writing, safe conduct out of the Maldives should the rebellion

fail.

An

alternative government was soon installed with Abdulla Afeef Didi

as executive head of state. The sterling-based economy boomed

and a degree of prosperity unknown in living memory emerged in

Addu. Afeef Didi's administration was based on democratic principles

hitherto or henceforth unknown in the Maldives. He did not tolerate

corruption.

Across

the channel in Fua Mulaku and Huvadu Atoll news of Addu's prosperity

quickly encouraged rebellion. On 13 March 1959 these two atolls

broke away from the sovereign authority of the Sultan of the Maldives

and joined Addu to form the United Suvadive Republic.

The

Maldives (then eqivalent of the) National Security Service

(NSS) Coast Guard in Huvadu Atoll 1961: state of the art

in naval technology |

The

reaction of the Sultan's government was swift and an armed gunboat

commanded personally by Prime Minister Ibrahim Nasir arrived in

Huvadu Atoll and quickly put an end to the rebellion in Huvadu

in July 1959. Similar measures were discouraged against Addu when

the British deployed a regiment from Malaya to Addu.

In

early 1960, a new agreement between the Bristish and the Sultan's

government was ratified. The British announced an end to their

backing of the rebellion. However the United Suvadive Republic

refused to be disbanded.

In

1961 Huvadu Atoll revolted again. Nasir personally appeared on

the scene again to quell the rebellion. This time the rebel headquarters

on Havaruthinadoo (Thinadoo) was completely destroyed and the

entire population dispersed from the island. Huvadu Atoll was

partitioned into two administrative regions- Huvadu East and Huvadu

West, later renamed Huvadu South and Huvadu North.

The

rebel leaders were jailed in Malé and many died

in very sorry and highly questionable circumstances. Among those

who perished were Ahmed Hirihamaanthi Kaleyfan and his son Abdulla

Kateeb. Hirihamaanthi Kaleyfan was arguably the wealthiest merchant

in the Maldives in his time. He was one of the last to be elevated

to a kangathi title.

The

supression of the second revolt in Huvadu and Fua Mulaku spelt

a body-blow on the United Suvadive Republic. The British were

by then actively campaigning against the Suvadive movement.

Prime

Minister Ibrahim Nasir's international diplomatic campaigns were

proving to be an embarrassment to the British.

On

22 September 1963, the British political agent in Addu spelt out

an ultimatum to the people of Maradoo to hoist the Maldive flag.

A man called Kubbage Ahanmaa found the design of the flag in a

book and made it with bunting supplied by the British. At 3 AM

on 23 September 1963, the Suvadive flag was cut down and the Maldive

flag hoisted over Maradoo by Elhadaithage Alifuthaa and Hassanrahaage

Ahanmaa.

Following

Maradu's capitulation, the British quickly spread the word that

only those who were under the sovereign authority of the Sultan

of the Maldives would be employed in British facilities. That

was the final blow on the United Suvadive Republic.

A

week later, Afeef Didi invoked the letter of protection from the

British authorities promising him safe conduct. The British honoured

the promise and evacuated him to the Seychelles.

Before

he left on 30 September 1963, Afeef Didi was ordered by the British

political agent to deliver the Maldive flag from Gan to Hithadoo.

As the flag was hoisted over Hithadoo and Afeef Didi sailed into

exile aboard HMS Loch Lomond, the United Suvadive Republic was

committed to history .

Gan

handover ceremony 29 March 1976: Flanked by the British

Ambassador to the Maldives, Vice President Koli Ali

Maniku receives the handover of Gan from Group Captain

W. Edwards of tne Royal Air Force. For the next two

years, March 29 was marked as the Maldives Independence

day until reverted back to July 26. Just above the Group

Captain's forearm is Mr Kakaagey Ali Didi who was appointed

as official in charge of Gan. He was later to become

my father-in-law |

|

In

Malé, Sultan Mohamed Farid proclaimed a general pardon

and no punitive action was taken by his Government against anyone

in Addu following the collapse of the United Suvadive Republic.

The

British withdrew from Addu in March 1976 and Maldive military

commitments to the United Kingdom and the Commonwealth formally

ended 19 years before they were due to end.

Afeef

Didi was pardoned by Velaanaagey Ibrahim Nasir Rannabandeyri Kilegefan

as President of the Republic. Afeef Didi visited Addu once before

he died in the Seychelles.

See

also:

Suvadive

Revolt

by

Michael O'Shea and Fareesha Abdulla

Home |