THE

MALDIVE ISLANDERS, A Study of the Popular Culture of an

Ancient Ocean Kingdom.

Price:

Euro 18 plus postage. Postage is 9 Euro outside of India.

Contact NOVA ETHNOGRAPHIA INDICA: ethnoind@hotmail.com

| INTRODUCTION

| EPILOGUE

|

VILLAGES

IN THE OCEAN

In the

low, lush tropical coral islands of the Maldivian Atolls,

villages were located in the middle of the island. Owing

to their independent spirit, Maldivians used to build their

homes in a haphazard way about the island. Thick coconut

groves and other vegetation encircled the human settlements,

so that no house would be seen from the sea. The only constructions

with a 'beachview' would be makeshift sheds for boatbuilding

or boat- repair and lonely 'ziyarat' shrines.1

There

are a number of reasons for hiding human settlements. Traditionally

Maldivians didn't think that it was good for a person to

look too much at the sea, because one's 'heart would turn

to stone'. This sentence, in Divehi means that one would

lose one's memory2 and become absent-minded, finding it difficult to concentrate

on, for example, reading, and not that one would become

merciless.

Furthermore,

many trees didn't grow well if the salt-spray hit them directly.

Therefore, the first barrier of resilient3 bushes growing close to the waterline and the second barrier

of coconut trees, would effectively protect the more salt-sensitive

plants growing in the interior of the island, like bananas,

papayas and breadfruit trees. For the same reason, paths

were narrow and winding, and the point where a path met

the beach was considered an important geographical feature

in the Maldivian settlement pattern.

Such

points were called fannu in Divehi, the language

of the Maldive Islands, and they were like the 'gates' or

'mouths' through which the village inside the island opened

itself to the sea. People went to the waterline with a purpose.

Men would go to the sea to fish, girls would go to the beach

to scrub pots, all people would go regularly to answer calls

of nature, and sometimes boys would go there to play. However,

unless there was a necessity to go there, people would stay

as much as possible in their villages inside the island.

The

interior of the islands back then was a green, pleasant

and cozy place, admirably described by H.C.P. Bell when

he visited the Maldives in 1922:

"'A

thousand trees towards heaven their summits rear' making

of the clean-kept peaceful roads "with leafy hair overgrown",

cool umbrageous "cloisters", almost continuous in their

extension. Houses there are in plenty, but so well embowered

and hidden by sheltering fences and skilful adaptation,

as to give the effect of a somewhat close-set rustic village;

with little suggestion of regular streets and habitations

(...) to mar the picturesque peaceful tout ensemble. In

roads, gardens, houses --no matter what or where-- "order

in most admired disorder" rules.4

However,

during the nineteen-forties, the self-contained world of

the Maldive islanders experienced a terrible shock. Mohamed

Ameen Doshimeyna Kileygefaanu, who ruled first as regent

(since 1944) of an absentee Radun5

and then as President of the first Republic he proclaimed

(in 1953, the last year of his rule), decided to build new

avenues in the islands. The drive was allegedly to 'give

a modern façade' to the country. However, given Mohamed

Ameen's highly militaristic inclinations, it was probably

a counter-insurgency measure (of preventive character, as

there was no insurgency within the country back then). Having

studied in Europe, the new ruler had knowledge of modern

warfare and introduced many reforms in the Maldivian military.

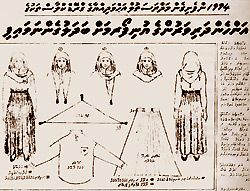

Mohamed

Ameen introduced leader cultism in the islands. He was the

first Maldivian leader that displayed himself wearing a

soldier's uniform: his portrait (see illustration) had to

be displayed in every office, public buiding and school

throughout the Maldive Islands. His desire was to have an

avenue in every island to stage parades where he himself

would be leading his modernized army. Soldiers were given

khaki uniforms to replace the ancient black-and-white feyli

waistcloth they used to wear.

Under

the direct supervision of Mohamed Ameen, the entire Maldivian

population, in every island of the country, was ordered

to work in the construction of wide, straight streets. They

were traced criscrossing every island from beach to beach

and many valuable trees were sacrificed in the process.

The punishments for any islander shrinking from work were

unduly harsh, as these avenues had to be built in record

time. Special government officers were dispatched to every

important island in order to check that the work was advancing

at a fast pace.

Thus,

menfolk were not allowed to go fishing and spent their days

working hard, felling and uprooting trees, digging and carrying

earth from one place to the other. Since no modern machinery

was used in the process, conscripted workers had to use

their bare hands or rudimentary small tools. Island people

said those were terrible times, that womenfolk and children

went hungry for lack of fish. I met the widow of a man who

was killed, tortured to death, in a punishing cell made

especiafly for those who disobeyed government orders and

went fishing or to gather coconuts to feed their families.

The number of people who died in those circumstances was

never recorded.

Islanders

failed to understand the rationale behind such broad streets

going literally from nowhere to nowhere and allowing the

deadly salt-spray to enter right into the heart of the island.

Traditionally, the paths within islands were winding and

shady and, according to the islanders it was a pleasure

to walk on them. Those paths were also winding, not only

to avoid the salt-spray, but also to hamper the movements

of certain evil spirits that moved in straight lines, like

the malevolent spirits of the dead ancestors (kaddhovi).6

However,

mostly, people were sore for having to sacrifice so much

badly needed good soil and the cool shade and the fruits

of different kinds the trees could offer. All individual

islands in the Maldives are very small (the largest being

barely 5 sq/km) and the total land surface of the whole

archipelago lies around a mere 300 sq/km. Considering that

there is so little of it, it is hardly surprising that land

is so precious in the Maldives. Therefore, practically all

Maldivians, except for a few staunch supporters of their

charismatic leader, Mohamed Ameen, considered the broad

avenues to be a pointless waste.

The

traditional pattern of urbanization was brutally disrupted

too. Maldive villages which had been originally clusters

of homesteads, every house auspiciously aligned towards

the proper orientation determined by the nakatteryaa

or astrologer, became long alignments of houses stretched

along the new avenues. All this had, and is still having,

unforeseen traumatic effects upon the vitality of the Maldivian

island society and many of those adverse effects have not

even been fathomed. The reason being that the traditional

position of the house and the orientation of its door in

relation of the cardinal points had a paramount influence

on social organization and attitudes.7

The

new streets had to be fringed on both sides by coral walls.

Thus, much sand, lime and coral stones were needed. The

new homesteads delimited by walls, increased peoples privacy

and did away with the custom of walking from one house to

the other through the spaces between house proper and kitchen.

This area was known as medugoti in most of the Maldives

and as medovatte in the southern end of the country.

Shaded by plantains, drumstick trees or fruit trees, the

medovatte was where Maldivians, who used to live

outdoors sharing the company of their neighbors, spent most

of their life.

Most

men and women in the Atolls claim that the new urban disposition

led to the exacerbation of island rivalries and to the loss

of community life. Many also blame the general growth of

pride, demoralization and selfishness among islanders to

the privacy and isolation of walled-in compounds. Thus,

much of the island social fabric was destroyed by such an

apparently harmless action as building new streets.

After

the traditional urbanization pattern was callously disregarded

and swept away by Mohamed Ameen, no one has come up with

an alternative idea. This misguided plan is, even now, the

only blueprint existing for island urbanization in the Maldives.

Therefore, the local Island and Atoll Offices throughout

the country keep still opening new straight, broad avenues

and enforce the building of walIs8 lining them, exactly as in Ameen's time.

In

1985, one teacher in Meedhoo, Addu Atoll, an island crisscrossed

by a broad, desolate and surrealistic looking avenue, glaring

white in the harsh tropical midday sun, told me that most

of his island's people thought walls were useless and didn't

see the point in building them. As coral stones and lime

were becoming rare, they were making a sacrifice to build

the walls, considering that some of their own little houses

were not even walled, but thatched. He concluded by saying

that the government "doesn't realize how poor some people

are."

All

these evils could have been avoided if the common people's

opinion had been valued or respected. Mohamed Ameen is now

considered to be a great leader in the official Maldive

propaganda. He is called 'The Great Modernizer.' However,

his methods were feudal: to build his avenues, all able

men in each island were recruited to do forced labor and

were not allowed to attend to their families. Every morning

the island men had to go to the empty space close to the

government office and stand in ranks. Then, at eight o'clock

they marched towards the road-building sites.

Anyone

who reported late, was beaten with a stick. One man said

that he had been given many lashes when he had been very

late. If someone refused to come he would be locked in a

small, stinking cell. Even though the actual republic was

proclaimed only in 1953, the last year of Mohamed Ameen's

rule, all those years are known as 'Jumhuri Duvahi'

(the days of the republic) in the collective memory of Fua

Mulaku people. According to one islander9

who lived through those times:

'When

we had to open the new avenues in our island, many of those

streets cut straight through marshy ground. Thus, we had

to bring sand and gravel from the beach in baskets to the

working sites. We also had to uproot the stumps of very

large trees. We used iron rods and ropes. Work was very

hard and we came back hot and exhausted. If we would have

been fishing or climbing coconut palms, we would have been

exhausted too, but at least we would bring fish or palm-sap

home. Now we were arriving home empty-handed. Many children

would die because of this. We were getting so little food

that we were forced to eat papaya stems, plantain roots

and different kinds of leaves.

The

men who worked were given very little, and bad food. Not

like the food you get at home. My neighbor was jailed after

he had been unloading sugar sacks from a vedi (trading

ship). He was so hungry he pulled a little bit of sugar

from one end of the sack with his finger. He was seen licking

his fingers by a supervisor and was reported. Then he was

brought to the kosi (jail) straight away. His wife,

an aunt of mine, went to plead to the authorities for his

release, but was rudely sent back home under threats. Prisoners

were given almost no food, they couldn't get the customary

daily bath and were given no medical treatment. Thus, my

neighbor died after a few months.

'When

we washed him for burial, we saw that his body was full

of horribly infected, stinking wounds. He was not the only

one to suffer that fate though, as many more people died

in that jail. A lot of women and children died of hunger

during those days too, sitting silently in their homes.Their

husbands were not able to bring any food home and they were

too terrified to complain to the authorities.

'We

didn't know why all this was happening to us. We were not

informed properly of anything. They said that there would

be less mosquitoes on the island, but we didn't understand

what all that heavy work had to do with insects, and anyway

there were the same amount of mosquitoes, if not more, afterwards.

Our old people, racking their brains for an explanation,

said: "Mohamed Ameen is the friend of the Englishmen. He

wants to kill us all and give our islands to them,10 so they will come here with their cars and lorries. That

is why he makes us build those avenues.'

Mohamed

Ameen is still a controversial figure in the Maldives and

his ten years of iron-fisted rule disgusted many islanders.

However, he had, and still has, a group of fervent supporters.

According to Koli Hasan Maniku, a local historian, his tenure

was a 'one-man-show.' On the one hand, he introduced necessary

reforms, but on the other hand, his contempt for the plight

of the common man in hard times earned him fierce enemies

all over the islands. It cannot be denied that he had a

vision for the future of his country, but he adamantly disregarded

advice and lacked the necessary imagination to adapt development

policies to the needs of the Maldive Islands. Thus, his

modernization campaign was perceived by the islanders to

be a brutally carried out implementation of his personal

whims and fancies.11

Last,

but not least, Mohamed Ameen showed the same contempt towards

autochtonous customs that Arab 'holy men', exalted to undeserved

high positions, had displayed throughout Maldivian history.12 The period of his rule is remembered as a long and difficult

decade by most islanders who had to live through it.13 Southerners claim that his harsh and insensitive policies

disgusted them with the central government. Therefore, it

is not unlikely that this resulting discontentment led,

less than one decade later, to the self-proclamation of

the Suvadive government in the three southernmost atolls.

This

secession was a belated antagonistic reaction, unprecedented

in Maldivian history, towards Mohamed Ameen's excessively

centralistic policies. The ancient absolute power of the

Maldivian Radun (which Ameen made not the slightest

effort to relinquish) coupled with with modern methods of

communication and control, translated itself into a Malé-centered

tyranny that stifled the traditional economy and the independent

and laid-hack island way of life. The Suvadive government

was born out of sheer bitterness, as ethnically and culturally

there was no justification for a division of the Maldives.

Notes:

1Nowadays,

owing to a very high birth rate and a drastic reduction

of the mortality rate, some islands have become overpopulated.

Naifaru, Hinnavaru and Kandoludu in the North of the country

are examples of islands completely covered by homesteads.

2Source

Magieduruge Ibrahim Didi of Fua Mulaku Island (1982).

3Boashi

(Messerschmidtia argentea) witn velvety grey-green leaves

and magoo or gera (Scaevola taccada) with fresh-looking

shiny yellowish green leaves. These bushes, common in every

Maldive island just need sand and seawater to grow.

4H.C.P.

Bell's Monograph, 'The Maldive Islands.'

5Radun

or Rasgefaanu is the traditional way of referring

to the Maldivian King. Sultan Abdul Majid was a Maldivian

gentleman living in Egypt who had no interest in going back

to his native country. Thus, Mohamed Ameen became the de

facto ruler of the country.

6This

metaphysical dimension points at the relationship between

the layout of the village and the need of sanctifying space

(Chap.1 'The First Mosques'). In the words of J.C. Levi-Strauss:

"We have then to recognise that the plan of the village had

a still deeper significance than the one we have ascribed

to it from the sociological point of view." 'Tristes Tropiques'

7J.C.

Levi-Strauss analyzed this phenomenon among an Amazonian tribe,

the Bororo. Colonists were aware of this fact and to stupefy

and neutralize the natives, they moved them to villages where

houses were arrayed in parallel lines.

8Since

the mid-nineteen-nineties some ecological laws have been

implemented to protect the reefs. The indiscrIminate

quarrying of coral stones has been restricted. Sand and

gravel (coral products too) keep being quarried for the

construction of walls though.

9I

have chosen to protect this person's identity.

10The

Maldives was then a British protectorate. However, Ameen

is officially considered a nationalist hero.

11In

spite of his 'modern' image, Mohamed Ameen's private life

was rather like that of a feudal despot, as he mantained

a large number of concubines from different islands.

12'Chap.

4 'Foreign Masters'.

13This

is a good instance of the wide gap that separates popular

sentiment and officially approved 'historical' records that

merely glorify the ruler. Fortunately, some people were

still alive to tell their side of the story at the time

of gathering this information.

The book is a good

investment. Grab it while it is in print!

rss feed

rss feed